Faecal worm egg counts

02 Mar 2022

In recent years, we have changed the way we worm (technically ‘de-worm’) our horses.

Instead of dosing at regular intervals throughout the year, we now realise that a targeted approach to individual horses is far safer and more efficient. A ‘one size fits all’ approach is no longer viable, as every yard has different risks depending on grazing strategies and numbers of horses coming and going.

There are 3 classes of worming drug on the market but sadly, due to their past overuse, only 1 remains fully effective. The worms have simply become ‘immune’ to the drugs. By testing horses and treating only those that need worming, and only when they need worming, we will keep the remaining drugs effective for as long as possible. No new classes of wormer have been developed so we must protect the capability of the ones we have.

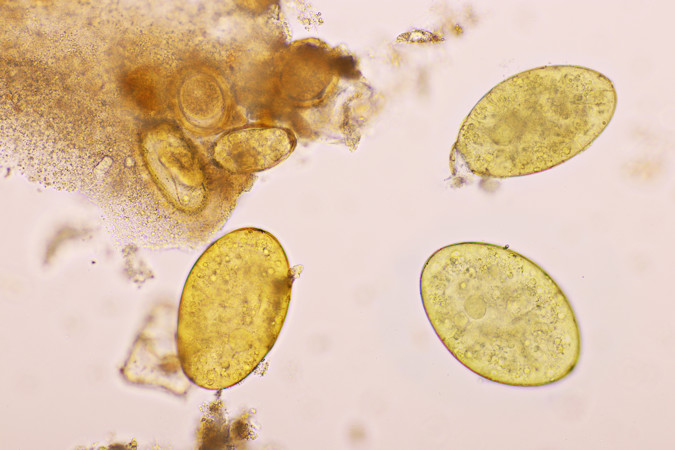

The most useful tool we have to ascertain which horses need worming, is a faecal worm egg count, or FWEC. Adult worms inside the horse’s gut lay eggs, which are passed out in the droppings. We can count these eggs by looking at the droppings under a microscope, and thus decide if a horse needs treatment or not. This count can be carried out quickly and cheaply at any time, but we use it for different purposes during the different seasons.

Spring and Summer

Warm weather means worms are active; growing and reproducing both inside your horse, and on the ground (hatching from eggs into larvae inside a dung pile).

Fresh droppings will contain any eggs from an internal worm population, and a FWEC will tell us how big that population is. 4-5 nuggets of droppings is enough for us to work with.

A FWEC should be performed at the start of Spring and then every 3 months throughout Summer into early Autumn.

Autumn and Winter

Worms tend to hibernate and cease activity during cold weather. FWECs are not routinely necessary during this time, but may be recommended if we have concerns.

Horses may be infested with different species of worm, broadly speaking these are large roundworms, small red worms and tapeworms.

FWECs have their limitations. They do not accurately pick up tapeworms, and cannot detect red worms if they have become encysted (trapped) in the wall of the horse’s gut.

A saliva test for tapeworm is recommended at least once during the Summer, but it must be carried out at least 3 months after any worming treatment.

A blood test for small red worms may be advised if your horse is at high risk, or is showing clinical signs of disease.

In any given population of horses, there are large variations in their immunity to worms. It is known that 20% of horses on a yard are responsible for 80% of the worm eggs shed in droppings. These 20% may never show clinical signs of a heavy worm burden, they just live with them. But they do infest the paddocks with vast numbers of eggs, increasing the risk of transmitting worms to others.

FWECs enable us to identify these animals and treat them accordingly.

Faecal Egg Reduction Tests

FWECs are performed, and then the same worming drug is given to all the horses in the trial. Second FWECs are carried out 14 days later. The number of eggs in the pre-treatment and post-treatment samples are used to calculate the percentage reduction in eggs for that drug.

Remember that all horses sharing a paddock share the same population of worms.

It is important to acknowledge that under-dosing of worming treatments, or failure to administer the full dose, may result in the incorrect assumption that a wormer isn’t working